|

| Cold War |

The cold war was the decade-long conflict between the United States and the Soviet Union, especially characterized by its constant tensions, arms escalation, and lack of direct warfare. First coined by author George Orwell to describe a state of permanent and unresolvable war, cold war was applied to the U.S.-Soviet conflict in 1947 by Bernard Baruch, the U.S. representative to the UN Atomic Energy Commission and influential adviser to both Franklin Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson.

Both sides often phrased the conflict as one between capitalism and communism, not simply between two states. Picking its endpoints requires some arbitrary choices, but it essentially lasted from shortly after World War II to the 1991 dissolution of the Soviet Union.

Long before even the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, there were significant differences between Russia and the West—Russia was a latecomer to capitalism, abolishing serfdom only in 1861—and the transition was an awkward one that created enough ill will to make a radical revolution appealing.

|

Before the 20th century, Russia’s imperial designs threatened those of Great Britain—a maritime rival—and Spain, which encouraged settlement in California out of fear that Russian colonists would settle the west coast traveling south from Alaska.

In both cases the Western nations may have been exaggerating or misperceiving the extent of Russia’s expansionist interests—just as was likely the case with Western perceptions of the Soviet Union during the cold war.

In the 20th century, the old European empires had lost their power, and the most powerful countries were the ideologically opposed Soviet Union and the United States, with its close ally the United Kingdom.

These were the two world leaders that developing nations would be shaped by and recovering nations would have to ally themselves with. Given the size and power of the countries—with perhaps as an additional factor the youth of their governments, relative to those of old Europe—some historians consider the conflict inevitable.

World War II had broken the faith that the Soviet Union had in the rest of the world’s willingness to leave communist states alone, and so Stalin sought to spread communism to neighboring countries in eastern Europe—Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary, and Poland—but remained uninvolved with communist interests in Finland, Greece, and Czechoslovakia, at least directly.

Winston Churchill was the first to refer to this band of communist countries as the “Iron Curtain,” referring not only to the fortified borders between the capitalist and communist nations of Europe but to the Soviet Union’s protective layer of communist states shielding it from capitalist Europe.

Meanwhile, communism grew in popularity in China, France, India, Italy, Japan, and Vietnam. Very quickly the West began to perceive communist victories as Soviet victories, and communist nations as Soviet satellites, officially or otherwise.

The United Kingdom could no longer afford to govern overseas and in the 1947 partition of India had granted independence to that holding, which led to the formation of the states of India and Pakistan. The United States began increasing its overseas influence as that of the British waned.

|

For the first few decades after World War II, the dominant focus of U.S. foreign policy was that of “containment”; the U.S. took pains to limit communist and Soviet influence to the states where it was already present and to prevent its “leaking out” to others.

Many believed that, so contained, communist governments would wither and die—in contrast, the domino theory proclaimed that if one capitalist government fell, its neighbors would be next, a proposition that motivated U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War, which was proclaimed a war not just over Vietnam but over all of Southeast Asia, which notably included former British and French holdings.

When civil war broke out in China, the Soviet Union aided the Communists, and the United States armed and funded the Nationalists. The new People’s Republic of China, formed on October 1, 1949, became a valuable Soviet ally, while the Nationalists took control of the island of Taiwan, from where they retained their seat in the United Nations.

The Soviets boycotted the United Nations Security Council as a result, and so were unable to veto Truman’s request for UN aid in prosecuting an attack on the Soviet-supported North Korean forces invading U.S.-supported South Korea. The Korean War that followed lasted three years, ending in a stalemate; into the 21st century no peace treaty had been formed between the two Koreas.

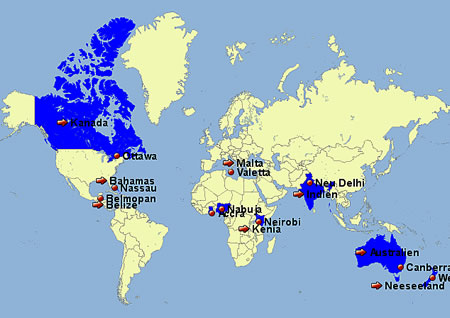

As the lines between the two sides became more clearly drawn, 12 nations formed the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)—Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Iceland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

In response to this and the rearmament of West Germany, Stalin’s successor, Nikita Khrushchev, formed a similar alliance of eastern European states called the Warsaw Pact: Albania, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and the Soviet Union.

Eisenhower to Reagan

From President Eisenhower in the 1950s to President Ronald Reagan in the 1980s the guiding light of military spending was deterrence theory, ensuring that retaliation would be swift and extraordinary. The specter of nuclear warfare dominated U.S. consciousness in these decades.

In the 1950s fallout shelters were built in many towns and private homes, and educational film shorts shown in schools included the famous “Duck and Cover,” in which a talking turtle advises children to seek shelter in the event of nuclear war. Many schools and town governments held duck-and-cover drills, which likely served no real purpose except to heighten fears.

Eisenhower openly worried about the inertia of the military-industrial complex as well as escalating military spending. Perhaps seeking to avoid future military conflicts, he was the first to use the CIA to overthrow governments in developing or less powerful nations that were unfriendly to U.S. policy, replacing them with nominally democratic ones.

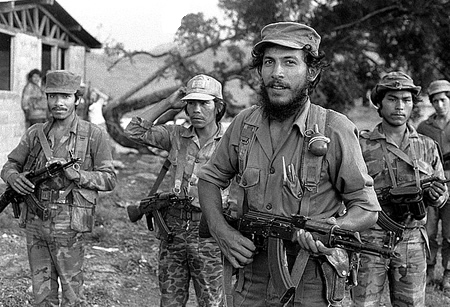

Asia, the Middle East, and Latin America became more important to the cold war than Europe. In Latin America, the United States had been involved in national politics since the 19th century, but the cold war gave a new lift to foreign policy.

As the increasingly powerful lower classes in many Latin American countries gave rise to a strong left wing and socialist concerns, the United States targeted revolutions and instigated coups against left-leaning governments.

Fidel Castro led the communist revolution in Cuba, only miles from the U.S. coast. The United States responded by dispatching a group of CIA-trained Cuban expatriates to land at Cuba’s Bay of Pigs and attempt to oust Castro from power.

The invasion was a significant failure and provided the Soviets with a further excuse to install nuclear missiles in Cuba—balancing out those the United States had installed in Turkey and western Europe.

Only when President Kennedy promised not to invade Cuba and to remove missiles from Turkey—close to the USSR—did the Soviets back down. It is still considered the moment when the two nations came closest to direct warfare.

Berlin Wall

In 1961 the Berlin Wall was built and quickly became the most vivid symbol of the cold war: The 28 miles of wall, barbed wire, and minefields separated Soviet-controlled East Berlin from U.S.-supported West Berlin. Passage across the border was heavily restricted.

Families were divided, and some East Berliners were no longer able to commute to work. About 200 people died trying to cross into West Berlin; some 5,000 more succeeded. It would be nearly 30 years before the wall came down.

By the end of the 1960s the prevalence of deterrence theory had led to a state of “mutually assured destruction” (MAD), in which an attack by either side would result in the destruction of both sides. Theoretically such assurance prevents that first strike, which was the logic behind limiting antiballistic missiles.

Talks and, later, agreements on strategic nuclear arms (SALT I and SALT II) began in 1969. President Reagan’s SDI program in the early 1980s would be a significant step away from the MAD model toward the goal of a winnable nuclear war.

The word détente—“warming”—is often used to describe the improvements in Soviet-U.S. relations from the late 1960s to the early 1980s, a time when military parity between the two had all but been achieved. Both nations’ economies suffered—the United States from the expense of the Vietnam War, and the Soviets from that of catching up to the United States in the nuclear arms race. In order to encourage Soviet reforms, U.S. president Gerald Ford signed into law the Jackson-Vanik Amendment in 1975, which tied U.S.-Soviet trade relations to the conditions of Soviet human rights.

The Soviets had lost their alliance with China because they had failed to strongly support China during border disputes with India and the invasion of Tibet. The prospect of facing a Chinese-U.S. alliance—however unlikely it may have seemed to Americans—discouraged the Soviets as much as MAD did, and contributed to their willingness to participate in summits such as those that resulted in the Outer Space Treaty, banning the presence of nuclear weapons in space.

As they recovered from World War II, western Europe and Japan became more relevant again to the international scene, as did Communist China. Especially from the 1970s on, the U.S.-Soviet domination of international affairs eroded. The United States began to come under more frequent and serious criticism for the choices it had made in its opposition to communism, especially for its support of dictatorial or oppressive right-wing governments.

Meanwhile, throughout the 1960s and 1970s, more and more developing nations adopted the policy of nonalignment. The Middle Eastern nations, their influence bolstered by oil and the increasing consumption thereof, became a particular factor, and the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), which increased oil prices in 1973 by 400 percent, was a leading player in the West’s economic troubles. As more countries joined the United Nations, the Western majority was broken.

In 1979 the secular democratic regime of the shah in Iran—supported by the United States and restored in 1953 with the CIA’s help—fell to an alliance of liberal and religious rebels, who installed the religious leader the Ayatollah Khomeini as the new head of state. Outraged at the involvement of the United States in Iranian affairs, a group of Iranian students held 66 Americans hostage for 14 months, until 20 minutes after President Reagan’s inauguration.

Détente ended as the 1980s began, with the Iran hostage crisis and the 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. Hard-line right-wingers had been elected in both the United Kingdom (Margaret Thatcher) and the United States (Reagan in 1981), and many neoconservatives characterized the détente of the previous decade as too permissive, and too soft on communism.

Just as the United States had come under criticism for its support of certain governments, the Soviets lost a good deal of international respect not only over Afghanistan but also when they shot down a Korean commercial airliner (Korean Air Flight 007, in 1983) that passed into Soviet airspace. The first years of the 1980s saw an escalation in the arms race for the first time since the SALT talks began.

The Strategic Defense Initiative, proposed by the Reagan administration in 1983, was a space- and ground-based antimissile defense system that would have completely abandoned the MAD model. Significant work went into it, seeking a winnable nuclear war, unthinkable in previous decades.

Mikhail Gorbachev

In 1985 the Soviet Politburo elected reformist Mikhail Gorbachev, the leader of a generation who had grown up not under Stalin but under the more reform-minded Khrushchev. Gorbachev was savvy, sharp, and politically aware in a way many Soviet politicians were not. The keystones of his reforms were glasnost and perestroika, policies almost encapsulated by catchphrases widely repeated both in the Soviet Union and in Western newspapers.

Glasnost, a policy instituted in 1985, simply meant “openness,” but referred not just to freedom of speech and the press but to making the mechanics of government visible and open to question by the public. Perestroika, which began in 1987, meant “restructuring.” Perestroika consisted of major economic reforms, significant shifts away from pure communism, allowing private ownership of businesses and much wider foreign trade.

Two years after the start of perestroika, eastern European communism began to collapse under protests and uprisings, culminating in reformist revolutions in Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, German Democratic Republic (East Germany), Hungary, Poland, and Romania. Several Soviet states sought independence from the Soviet Union, and Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania declared independence. The period culminated in the fall of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989.

After years of public pressure, East Germany finally agreed to lift the restrictions on border traffic for those with proper visas. East Germany had little choice but to abandon the wall. They did nothing to stop the Mauerspechte (“wall chippers”) who arrived with sledgehammers to demolish the wall and claim souvenirs from it, and began the rehabilitation of the roads that the wall’s construction had destroyed. By the end of the year free travel was allowed throughout the city, without need of visas or paperwork. A year later East and West Germany reunified.

In 1991 radical communists in the Soviet Union seized power for three days in August, while Gorbachev was on vacation. Boris Yeltsin, the president of Russia, denounced the coup loudly and visibly—standing on a tank and addressing the public with a megaphone.

The majority of the military quickly sided with him and the other opponents of the coup, which ended with little violence. But it was clear that the Soviet Union would not last—it was soon dissolved, becoming 15 independent states.

With the dissolution of the Soviet Union the cold war was technically over, effective immediately, but a “cold war mentality” continued. The United States continued to involve itself in international affairs in similar ways, sometimes being accused of acting like a world policeman—a role the United Kingdom had enjoyed before the world wars.

The apparatus of espionage found new subjects, with the ECHELON system of signals intelligence—monitoring telephone and electronic communication—eventually repurposed for the war on terror following the 9/11 attacks in 2001. Contrary to every expectation, the cold war ended without direct warfare and without the use of nuclear weapons.